Seeds of hope

- Sep 16, 2025

- 5 min read

Words by Jamie Crocker

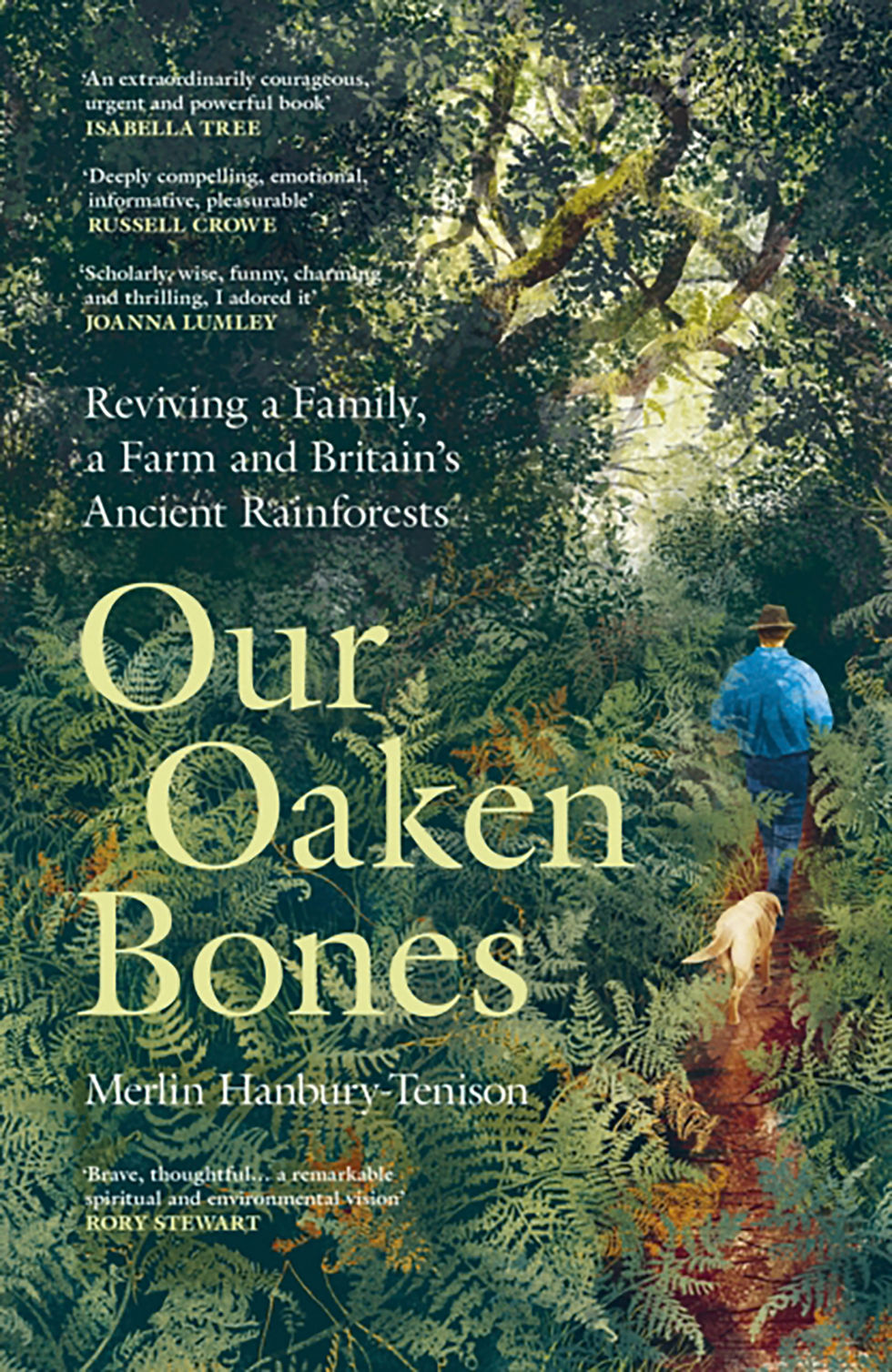

One man’s dream for the future shapes a book that points towards a better world we can all help build.

The announcement arrived at nine o’clock on a Tuesday morning in August: Merlin Hanbury-Tenison’s debut book, Our Oaken Bones, had been shortlisted for the Wainwright Prize. For a first-time author who never studied English beyond GCSE level, this recognition represents something extraordinary. Yet his journey to published author began not in lecture halls or writing workshops, but in the harsh realities of three military deployments to Afghanistan, where a young soldier’s certainties about war and righteousness slowly crumbled.

“I was 21 years old and brainwashed,” he reflects of his first tour, using a term that might surprise those expecting conventional military pride. “The whole point of military training is to make you think that your army is the best and greatest. But by my third tour, I was working closely with the Afghans and the Taliban and I began to realise that we were all the same. We were just looking at the world through a different mirror.”

This realisation – that warfare achieves nothing beyond building political careers while damaging both nations involved – fundamentally shifted Merlin’s worldview. The contrast between the trillion dollars spent over 20 years in Afghanistan and what might have been achieved through schools, dams, and educational programmes became a recurring theme in his thinking about systemic change.

Now running a charity – the Thousand Year Trust – and managing a temperate rainforest in Cornwall, Merlin has channelled these hard-won insights into his debut book, a meditation on nature restoration that deliberately avoids the traditional environmental extremes. Unlike the radical approach of writers like George Monbiot – whom he deeply respects but doesn’t entirely follow – he advocates for what he calls “the course somewhere down the middle.”

“We need to break a bit in order to stop destroying the natural world,” he explains, “but do we need to break everything? Do we need to totally tear up the system that’s been running for a few hundred years now?” His answer, shaped by witnessing the traumatic consequences of sudden regime change in multiple countries, is decidedly no.

This measured approach extends to his writing philosophy; he deliberately avoided formal instruction. “I believe that all of these courses inevitably push people towards a common standard,” he argues. “What makes writing beautiful when you read people like Robert Macfarlane is that they have a very distinctive, unique style. So I’ve tried to write how it feels normal, how I would speak.”

TOP LEFT: Where folklore and childhood tales abound

TOP RIGHT: The Bedalder

ABOVE: The ‘Mother Tree’

The strategy appears to have worked. Readers consistently tell him the book captures his speaking voice perfectly, a quality that emerges from his conviction that authenticity trumps technical perfection. This philosophy reflects a broader critique of modern education systems that prioritise calculus over cooking, engineering over home economics – a shift that Merlin sees as contributing to everything from obesity rates to environmental destruction.

The book’s central thesis revolves around what he calls “the job of a farmer” – though he believes the terminology itself needs updating. “They need to be land stewards,” he insists. “Ecosystem services plus timber production, plus food production, plus beautiful places that people spend time.” This multifaceted role becomes crucial when examining Britain’s stark agricultural statistics: twenty-two per cent of UK land is used for sheep farming, yet provides less than one per cent of our calories.

Such figures fuel Merlin’s argument that Britain’s food security concerns are largely misplaced. “We produce fifty-eight per cent of our food. We waste one-third of all food produced. Sixty-four per cent of people are overweight or obese. We don’t have an issue with food production. We have an issue with food wastage and choice.” The solution involves shifting towards predominantly plant-based diets with occasional local meat consumption – not through heavy-handed legislation, but through education and subsidy reform that reflects true environmental costs.

TOP LEFT: Merlin and his father, Robin

TOP RIGHT: The Hanbury-Tenison 'family'

This pragmatic environmentalism stems partly from his military experience with sudden systemic change. Farming already has one of the highest suicide rates in the UK, he notes. Tearing up the current system overnight would likely worsen this tragedy. Instead, he envisions change happening across generations, embodied in his concept of ‘the thousand-year project.’

The timeframe isn’t arbitrary. Looking back five thousand years to when humans began abandoning earth-goddess worship for sky-father religions, he identifies the moment when “we stopped respecting what was beneath our feet and viewing ourselves as self-appointed overlords.” This spiritual dimension distinguishes his environmentalism from purely technical approaches, though he’s careful to ground it in practical considerations.

“How do we recapture that connection in line with a global capitalist community?” he asks. “Can we go away from idolising some fictional sky god and start idolising the ground beneath our feet? But do it in a way that doesn’t mean we have to tear up the whole world and all go and live in communes?”

TOP: Nature Library

ABOVE: A place for meditation and healing

This tension between spiritual reconnection and practical systems runs throughout Our Oaken Bones, reflecting Merlin’s broader rejection of binary solutions to complex problems. Whether discussing capitalism versus socialism, conservation versus agriculture, or legislation versus education, he consistently seeks middle paths that acknowledge multiple truths simultaneously.

The approach emerges partly from personal experience. His relationship with his father, an explorer often away on expeditions, required similar nuanced navigation. Despite the significant age gap and limited bedtime stories, they’ve built a strong relationship around shared interests in reading, writing and conservation. “I’ve had to put a lot of work into accepting him for who he is,” Merlin explains, “and meet him where he needs to be rather than expecting him to be anything other than he is.”

This acceptance philosophy extends to his environmental work. Rather than demanding immediate perfection from farmers or consumers, he advocates for gradual change that protects people throughout the transition. The same patience applies to his thousand-year vision, which he describes as “a pathway towards optimism” – a deliberate counter to the environmental despair narrative.

“Within a thousand years, I have no doubt that we will probably have a smaller population living more in harmony with nature,” he states. “We will have wolves and beavers and lynx and all the other things we lost, and we’ll have a lot more rainforest. The journey we take to get there is our decision. Do we want it to look like a timeline with lots of war and plague? Or can we choose to get there without that conflict?”

For Merlin, writing Our Oaken Bones represents part of this gentler transformation process. By sharing his evolution from convinced soldier to thoughtful environmentalist, he offers readers permission to change their minds without losing face. In a polarised world where admitting uncertainty often seems like weakness, this intellectual honesty feels revolutionary – even if he’d probably prefer the term ‘evolutionary.’

He hopes readers will tell him they’ve read it and share their thoughts. Because for him, purpose and practice are inseparable – he is the gentle evangelist for change. And that conviction, aligned with where we find ourselves in this epoch, is what makes this book very necessary. One that we should all read.

Experience the restorative powers of nature and book a retreat at Cabilla or find out more about The Thousand Year Trust by visiting their respective websites. Merlin’s book is widely available from booksellers throughout the UK.